- Home

- Grace Zaring Stone

The Bitter Tea of General Yen Page 4

The Bitter Tea of General Yen Read online

Page 4

“Persuaded!” exclaimed Mrs. Jackson. “You couldn’t persuade that woman. It is a pity, I think, to feel you know everything in this world.”

“Well, dear, I shouldn’t say her disagreeing with me constituted a claim for universal knowledge. Should you, Miss Davis?”

He smiled again under his long mustache, and Megan smiled back at him. She felt sure he had had a hard afternoon with Miss Reed.

“Is the orphanage in any real danger, do you think?” she asked.

“It is hard to say, but it very well may be. There seems to be no doubt that the Chinese will take Shanghai. The Concessions are too well defended to be harmed. That is, they are now. If this were happening two months ago it would be a different story. But I feel sure it will go hard in the Chinese city and the outlying districts. If Miss Reed and her orphanage were in my charge, I’d order her to leave.”

“I wonder why she won’t come.”

“She won’t come,” said Mrs. Jackson, “because people have told her it is unsafe and she loves to disagree with them. She loves nothing better than being in danger and then saying, ‘Oh, it was nothing, it was nothing really.’ ”

“My dear, you must not be so bitter and critical. Miss Reed is a good woman.”

“Well, so am I a good woman,” said Mrs. Jackson emphatically, and Mr. Jackson said nothing but sighed and twisted a little sadly the drooping ends of his mustache.

“Besides,” said Mrs. Jackson, “I don’t see why you insist she is as good as all that. She loves making herself and every one around her miserable. She has put herself and another lady and a lot of children in danger of their lives and she puts you to no end of trouble.”

“Oh, come, come,” said Mr. Jackson, and he went over to his wife, awkwardly patting her on the shoulder. “Suppose I get you an aspirin,” he said.

The classification of a good woman, surely a classification that was now fairly obsolete anyway, disturbed Megan, but she knew he meant it only as testifying that Miss Reed was unquestionably physically pure. She thought perversely of the concubines of General Yen Tso-Chong and wondered if intolerance sometimes fails because even though honorable and vigorous it can often overlook an essential point. Miss Reed made every one miserable. Perhaps the concubines did not. What was the essential point? Megan gave it up.

After dinner Megan went to her room early, and read in bed for some time. She had a book of Papini, Perugia’s Peintres Chinois, and an old book on Jesuit missions in China and Japan full of old engravings. But she could not concentrate on any of them. She wrote a long letter to Bob telling him of her arrival, of the Jacksons, of the episode of the wrecked car. Then she turned off her light. Her open window now was only a square in darkness but it brought her the odor of the night. She wondered if there really could be a difference between this smell and that of rainy nights at home; this too was herby and clear, a new smell, but into the room crept a strong under-taint of fertilizer suggesting sickness and age. It came somewhere from the great plain beginning outside her window, a plain that has supported life for such countless ages one wonders it has any power left to force out a single fresh shoot. Megan, already tired, felt the oppression of such a burden; on her relaxing consciousness the sheer immobility of it pressed heavily, pierced through now by the young, quickening jets of rain.

IV

The next morning early Megan went to her window. The rain had momentarily stopped, but the sky was gray and low and it would surely rain again. Along the muddy road passed the Chinese, pushing heavily laden wheelbarrows or sitting in rickshaws holding bundles bigger than themselves on their laps. Even motor-cars were bulging with mattresses, sewing-machines, stoves, all those possessions which are accepted without thought but which when dragged out of the houses where they belong give such a pitiful exposure of the actual simplicity of our needs. Mr. Jackson was right; the rush for the Settlement had begun.

It was Sunday. After breakfast they rode to church in rickshaws, with the hoods up and leather aprons fastened across them by patched-up loops of string. It was raining a little. Megan had never been in a rickshaw before and she did not feel the horror she had anticipated at being pulled along by a human being. The coolie had muscled bare legs and he swayed from side to side with a faint trace of swagger; the odor of garlic he had been eating came cheerily back to her. There was something about the equipage, disreputable as it was, that gave her a feeling of pomp and circumstance not entirely unpleasant.

They passed the entrance to the Avenue Joffre, going along the road edging the Settlement, to the Avenue Haig. On their left heavy coils of barbed wire shut out a few mean Chinese houses, a large Chinese building behind a brick wall, with an institutional look about it, farther on making a barrier to dreamlike vistas of water-soaked fields, canals, and low Chinese farmhouses with roofs horned like the new moon. They turned to the right at the side of a large riding-school with paddocks and an enclosed ring. A huge tow-haired Russian groom was leading a horse from the ring.

The church was bare. Only Europeans were there, and they got up, sat down, made the responses with what seemed a determination wearier but more dogged than it would have been at home.

“Let me never be confounded,” sang the choirboys in their white, reedy voices.

In the afternoon Mr. Jackson went off to try to persuade Miss Reed for the last time to evacuate the orphanage. Mrs. Jackson expressed the belief that he would not succeed.

“I wish Doctor Strike were here,” she said to Megan. “He could make her do it. But Will never can; he is afraid of her.”

She added that Doctor Strike might be expected at any moment now, and every time the telephone or the door-bell rang she said, “That is probably the Doctor now.” But he did not come.

The afternoon passed interminably to Megan. She longed to be out helping Mr. Jackson evacuate the orphanage. She envied Miss Reed, who at least was in the midst of the storm. It was so hard sitting still and watching Mrs. Jackson knit, trying to talk to her. After she had shown Mrs. Jackson her trousseau, which Mrs. Jackson evidently found much too plain, and had answered a few questions of “what they wore” at home, they really had nothing to say to each other. Toward the one subject on which Megan tried to draw her out Mrs. Jackson maintained an evasiveness that had a flavor of positive resistance. In her rambling sentences she would sometimes mention casually and without explanation, as if every one must have heard of them, such persons as Doctor Strike, Mrs. Walsh at the Socony Installation, Miss Reed, her amah who was devoted to her, but she could not be induced to talk about China. She had not a trace of intellectual curiosity. If there were things in the world mysterious and a little terrifying, she would refuse to be either mystified or terrified, she would blank them off. And China she ignored as if it had been an obscene fact of life, like sex. Megan tried to imagine her sitting for the last twenty years in a Chinese house, eating Chinese food, speaking Chinese and ignoring China.

Seeing Megan was restless, Mrs. Jackson asked her if she cared about reading, and when Megan answered that she did, Mrs. Jackson went up-stairs and returned with a book.

“I find this very helpful,” she said, handing it to Megan.

It was a small, thin volume printed in 1884 by some mission press in Calcutta and it was called A Noble Life. Megan looked through its yellow pages and saw it was an account of the life of Archibald Alexander McPherson, who left the British army to engage in mission work in India. As Megan read here and there to see if she might discover what had been the force that had driven him to do this, she came on sentences like these:

“He became more and more sensitive to sin. On one occasion he corrected his native boy for some fault with more sharpness than he afterwards deemed necessary and when he became convinced that he had given way, even in a slight degree, to anger, he called his servant and falling on his knees begged his forgiveness with tears of contrition.”

Megan looked up at Mrs. Jackson with astonishment. She now pictured her on her knees before the

number one boy, begging his forgiveness with tears of contrition. And even Megan smiled. Mrs. Jackson and Archibald Alexander McPherson both had a knowledge, perhaps equally unerring, of their own needs, and Mrs. Jackson was not to be diverted by any pleasing fantasies she might profess; she remained untroubled by such mystic pressures as tormented Archibald Alexander McPherson.

As Megan sat pretending to read, the telephone rang again. It turned out to be a young naval officer she had met on the boat whose name was Bates. He wished to take her to dinner. She had not particularly liked him but after a slight hesitation said yes. She explained him to Mrs. Jackson as a pleasant sort of fellow who had come out to command a gunboat and would leave the next day for up-river. Mrs. Jackson did not understand why an engaged girl wanted to dine with another man, especially on Sunday.

“I’m really not endangering my future happiness. And certainly I ought to begin to know something of China.”

“I don’t think the wife of a mission worker needs to know the China that a gunboat commander is going to show her.”

“Are they so dreadful?” asked Megan, smiling.

“I think they’re pretty loose in their morals, though there was a nice one evacuated us out of Shasi.”

Lieutenant-Commander Bates took her first to the Palace, where they could sit and watch the lights of the warships anchored along the Bund—English, French, Dutch, Italian, Japanese and American. Megan looked at the American cruiser with pride. More than any of the others, of course, it contained steel, discipline, honor, handsome men and sudden death.

“Have a cocktail,” said Bates.

“Thanks, I believe I’ll have a glass of sherry.”

“Better have a cocktail. I knew by your voice over the telephone that you thought you should not come. I see by your face you wish now you hadn’t. Suppose you be as reckless as you can and I’ll be as careful as I can and perhaps we’ll strike a mean.”

Megan was regretting she had come; in saying yes she had been headlong, thinking only of a momentary escape from the dear Jacksons, forgetting that she might find Bates’ society infinitely more trying. She was so stiff and formal that Bates himself began to have regrets. He said to himself that she would be completely wet, and to brighten up the prospect a bit he drank three Martinis.

They started for a place some one had assured him was amusing. Megan wanted to ride in a rickshaw so they ambled up Nanking Road in the rain, a European street of European shops, harshly lighted, with glimpses down narrow side-streets of more diffused lights and fluttering banners. Farther along the shops became all Chinese and suddenly the street was a blaze of lighted turrets and towers. On Bubbling Well Road opposite the dark emptiness of the Race Course they found the place they were looking for.

In the cloak-room a flock of Chinese women fluttered about her. They wore evening coats with great ruches about the necks and underneath a hybrid garment, half of Europe, half of Asia, the costume of the treaty port, a long coat dress with a stiff high collar. They were thin, fleshless, with the bones of birds, their lacquered hair cut short like men’s, their skins seeming without pores, mat, delicately yellow. Some had brought small children, dressed and painted as miniatures of themselves. In the café they sat about in chattering groups, and when the music began they fox-trotted and Charlestoned with Chinese men in evening clothes or long skirts. There were an equal number of Europeans about and the place was full of smoke and jazz tunes. Down a long stairway at one end some strong men, coated with liquid powder and draped in leopard skins, postured under a white spot-light. Bates found a table, and Megan resigned herself to enduring Bates and the jazz and the Jewish strong men. It was the things which made it like a dinner at home she found hard to endure. But there was so much noise they did not have to talk much, and a certain amount of time was passed in dancing.

Bates said: “We’ll see nothing like this up-river, better enjoy ourselves while we can.” For Bates considered them fellow victims. “What do you suppose your missionary crowd would think of this place?”

“I suppose they’d be shocked. They are not out here for this, you know.”

“I’m willing to believe that. I’m very broadminded myself, but I don’t see where their jobs would be if there weren’t things to shock them going on. You really have to look at that side of it, don’t you?”

“Yes, I suppose so.”

“You do now. Then there is this side of it: why don’t they turn to on some of the white population, do a bit for the Russkys, say? There are thousands and thousands of them here, all out of work and selling themselves and whatnot. Look at that one over there for instance, rather easy to look at and undoubtedly on the road to Gehenna.”

There were plenty of Russian faces, but the girl Bates meant sat by herself at a table near them, getting up every now and then to dance with whoever asked her. The men who came over to her from other tables were in general as self-conscious as though they had been asked to go up on the stage and help a conjurer, but the girl was somber and half asleep with exhaustion. She was overly buxom, dressed in a too thin, soiled, flowered chiffon dress. Her hands were dirty, but her eyebrows met in an exquisite scimitar arch over black eyes like those in Persian miniatures. Her head was beautiful in a way that was almost an affront. Bates did not really admire her, he was accustomed to prettiness groomed and moderated; she was beauty in the raw. Still she disturbed him and he went on looking at her. Megan’s mind flashed back momentarily to the Chinese woman she had seen in the car with the chenille fringes, the car that had stopped at the scene of the motor wreck. She remembered against the Russian woman’s look of submerged revolt the Chinese woman’s air of modesty and complete acceptance of living.

“That girl is too fat but she has got a good nose,” Bates continued. “That is what is the matter with these Chinese women. No noses.”

“They have rather Egyptian noses, haven’t they? And they are rather alike, come to think of it, both agriculturalists for thousands of years and peace-loving. I suppose it is natural for an agriculturalist to be peace-loving. But can there be any connection, do you suppose, between agriculture and noses?”

“Well, I’m not prepared to say. Let’s dance. You wouldn’t think,” he said as they worked through the crush, “that this city is going to be captured in a few days, would you?”

“But is it? And will it make a great difference?”

“Bound to be. And it will make plenty of difference to the Chinks. Don’t you worry though. We’re looking after the Concessions. You can give us credit for that, noses or no noses.”

The evening stretched in front of her like a tunnel. The continuous blare of sound, the smoke, and across from her the fatigue and scorn of the Russian woman, who never ceased to dance with whoever asked her and to say at intervals, “One small bottle wine, please,”—these things became insupportable. Feeling that it must be nearly morning she stole a glance at her wrist-watch and found it was only quarter past twelve.

“I must go now. The Jacksons will worry if I am out late.”

“Good girl. Must get good girls home early. Boy, bring chit.”

But he had time to consume another whisky soda. He was becoming agreeably boisterous, he laughed at everything she said.

“Perhaps after all I’ll have a chance to sack a city. Can you see me doing it? Can you see me tearing jade earrings off the shrieking women? Can you?”

“No, I can only imagine you rescuing them in the orthodox manner.” But the truth was she did not want to imagine Bates in China at all, and it was a matter of complete indifference to her what he did or did not do.

In the lobby he tried to persuade her to go on to some other place with him. There was a Russian club just outside the Settlement where they had real vodka and served the meat on a bayonet, and another place where they had a roulette wheel.

He was like a child in his desire for entertainment and in his dependence on some one else for it. He was even dependent on Megan now that they had had dinner

and a few drinks together. But she would not stay.

When he deposited her at the house she found Mrs. Jackson sitting up for her.

“Did you have a nice time?” she asked.

Megan admitted that she wished she had not gone.

In her own room she decided to have a bath and turned on the water so that the little bathroom was a cage of steam. She had an idea of washing away the unpleasant impression the evening had left with her, but in the tub she felt more depressed than ever. Clothes are more of a protection to us than we realize until we take them off. When we take off our clothes we take away at the same time all the evidences of the rôle we have chosen; we are very apt to lose our dignity and even our purpose, and for the moment to sink back into an indistinguishable humanity. Megan lay in the warm water feeling that this poor stripped creature that was herself was not worthy of her vocation.

In her bed she propped up the pillows and picking up the account of the early Jesuit Missions ruffled the pages back and forth, thinking of the view she had just had of the European excrescence on China. It was obvious that white Shanghai must be chiefly composed of homes full of honest citizens like any other city, like Indianapolis, like Dijon, like Brighton, probably as nearly like them as it could possibly be made. But the dulness of the entertainment she had taken part in was doubly dull, seen as a transplanted thing, just as the stoves and sewing-machines of the refugees had seemed particularly pitiful as things one felt compelled to drag with one from place to place.

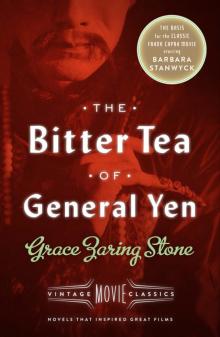

The Bitter Tea of General Yen

The Bitter Tea of General Yen